Evolution is a master recycler. It often uses old structures (or ancient genes) for new jobs. The mammalian ear is a perfect example. Over the eons, the jawbones of our fish ancestors became three separate small bones that transmit sound waves from the eardrum to the inner ear.

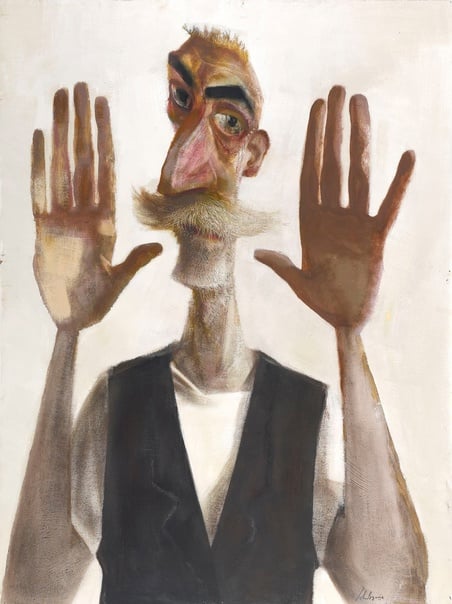

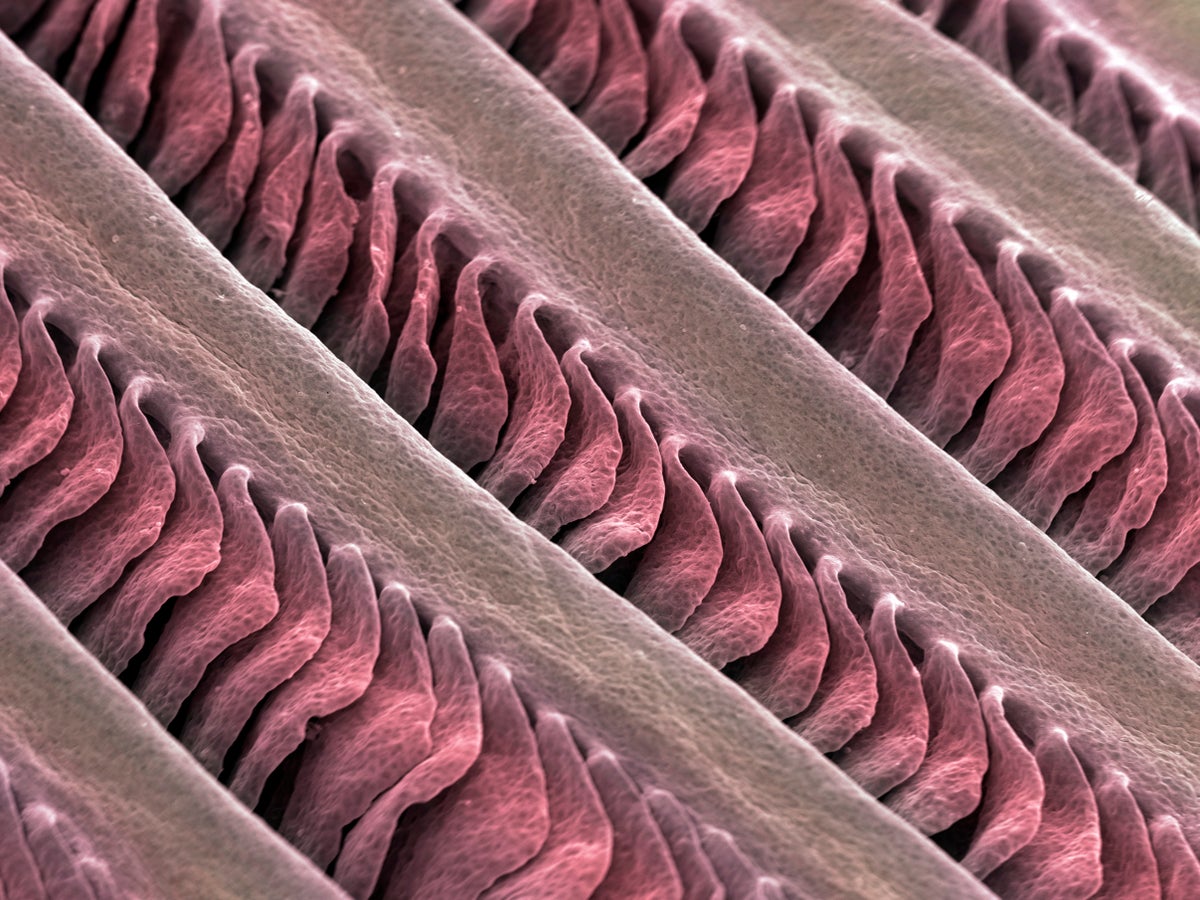

Now a new study shows that there was another hand-me-down from fish to mammals. It turns out that the flexible cartilage of fish gills bears a close correspondence to the cartilage in the mammalian outer ear, the visible part of the ear. To be sure, flexible cartilage structures take on different jobs in fish and mammals: the gill structures enable fish to breathe while the cartilage in mammals’ outer ears captures sound. But the underlying gene network that builds these structures shares a common history.

To be clear, the gill structures did not morph into the mammalian outer ear. Rather, as the first vertebrates emerged on land and dispensed with gills, the underlying network of genes that formed the gill cartilage was able to build something new.

I just finished reading Your Inner Fish by Neil Shubin and it goes into the many changes our ancient ancestors underwent over hundreds of millions of years to arrive at human anatomy. It’s really fascinating how paleontologists and biologists study fossils to put all the pieces together.