As computer programmers, our code runs on a wide variety of machines. From 2TB of RAM dual-EPYC servers with 128+ cores/256 hardware threads, to tiny single-core Arduinos running at 4MHz and 4kB of RAM.

While hobbyists and programmers around the world have become enamored with Arduinos, ESP32, STM32 Pills, and Rasp. Pi SBCs… there’s a noticeable gap in the typical hobbyist’s repertoire that should be looked at more carefully. This gap is the entry-level MPU market, perhaps best represented by Microchip’s SAM9x60, though STM’s STM32MP1, NXP i.MX ULL, and TI’s AM355x chips tightly compete in this space.

I hope to muse upon this category of processors, why its unpopular but… why maybe today, you should give it a closer look.

Impedance-controlled 6-layer PCBs USED to be too complex for a hobbyist… but they’re accessible today

This section’s title says it all. Typical MPUs require PCB complexity that… at least 10 years ago, was well beyond a hobbyist’s means. In the 2010-era of the fledgling “Maker” movement, 2-layer PCBs were the most complex you could hope for. Not just from a manufacturing perspective, but also from a software perspective. EagleCAD just didn’t support more layers, and no manufacturer catered to hobbyists to make anything more complex. Paying for $500 NRE fees each time you setup a board just wasn’t good on a hobbyist’s budget.

But today, OSHPark offers 6-layer boards (https://docs.oshpark.com/services/six-layer/) at reasonable prices, with tolerances specified for their dielectric (and therefore, impedance-controlled boards are a thing). Furthermore, KiCAD 7+ is more than usable today, meaning we have free OSS software that can lay out delay-matched PCB traces, with online libraries like UltraLibrarian, offering KiCAD Footprints and Symbols sponsored by Microchip/Ti/etc. etc. There’s also DKRed’s 4-layer service, JLCPCB’s services from China and plenty of competitors around the world that can take your 6-layer+ gerbers and give you a good board.

We live in a new era where hobbyists have access to far more complexity and can feasibly build a bigger electronics project than you ever dreamed before.

The classic team: Arduino and Rasp. Pi…

Arduino and Rasp. Pi stick together like peanut butter and jelly. They’re a barbell strategy providing the user with a low-cost, cheap, easy-to-customize chip (ATMega328p and other Arduino-level chips) operating at single-digit mW of power… with a large suite of analog-sensors and low latency and simplicity.

While Rasp. Pi offers Linux-level compute solutions, “grown up” C++ programs, Python, server-level compute. Albeit at the 6W (for Rasp. Pi 4) or beyond, so pushing the laptop-level power consumption. But… that gives us a good team that handles a lot of problems cheaply and effectively.

Or… is it? This barbell strategy is popular for good reasons from a problem-solving perspective, but as soon as any power and/or energy constraint comes up, its hopelessly defeated. Intermediate devices, such as the ESP32 have popped up as a “more powerful Arduino”, so to speak, providing more services (WiFi / Bluetooth, RAM and compute-power) than an Arduino can deliver, but is still far less than what Rasp. Pi programmers are used to.

What does a typical programmer want?

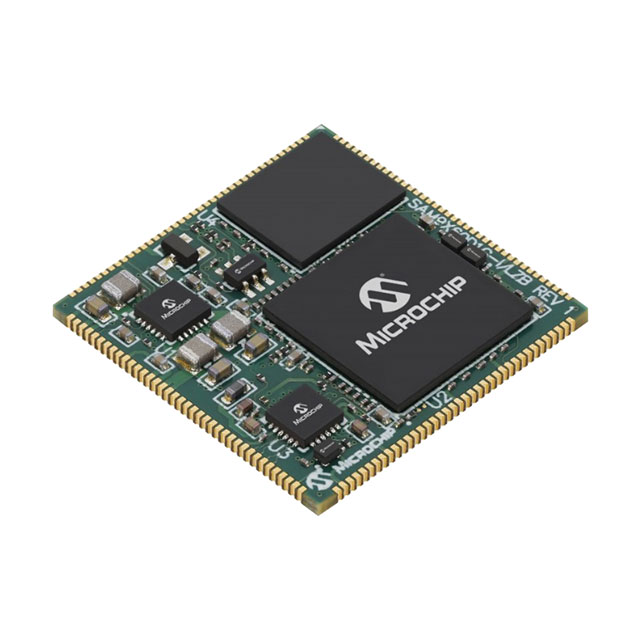

SAM9x60: ARMv5 at 600MHz, 128MB DDR2, Linux 6.1.x, dual-Ethernet 10/100, USB in 30mm x 30mm

When Rasp. Pi launched a bit over 10 years ago with 256 MB and a 700MHz processor and full Linux support, it set off a wave of hobbyists to experiment with the platform. Unfortunately, Rasp. Pi has left this “tier” of compute power, chasing the impossible dream of competing with Laptops / Desktops. IMO, the original Rasp. Pi 1 hit a niche and should have stuck with that platform. Fortunately, alternatives exist today.

Though the SAM9x60D1G-i/lzb SOM Module above is far more complex than a Rasp. Pi, its a good representation of what’s possible with a modern entry-level MPU. Yeah yeah yeah, its $60 but stick with me a bit longer. The SOM module is a bad value, but it shows the minimal system that it takes to boot this chip. This is very different from Rasp. Pi indeed.

SAM9x60 chip is fully open source, and fully documented at https://linux4sam.org. You get a full builtroot environment, a fully documented stage1, stage2, and stage3 (UBoot) bootloader. You get all 2000+ pages of documentation. You get PCB layouts, you get fully open source Linux drivers and kernel modules. You get the full “make” available from Microchip’s github. The openness to this chip is insane, especially if you’re used to Rasp. Pi.

And perhaps most importantly: SAM9x60’s reference design fits on 4-layer boards. (This is an INCREDIBLE feat of engineering. Microchip has spent a lot of effort simplifying this 233-BGA chip and trying to get it onto the simplest means possible). Note however, that I’d personally only be comfortable with a 6-layer design here. (SAM9x60’s reference design is signal/ground/power/signal stackup, which is frowned upon by modern PCB theory. signal/ground/power/signal/ground/signal would be a superior stackup… and 6-layers is cheap/available today anyway, so might as well go for 6-layers). In any case, the 4-layer demonstration reference board (https://ww1.microchip.com/downloads/en/Appnotes/AN_3310_Connecting-SDR-and-DDR-Memories-to-SAM9X60_00003310a.pdf) is far more documentation and discussion than you’d ever hope to be released by the Rasp. Pi group. The openness to this platform is like night-and-day.

At $8 per SAM9x60 and at $3 to $5 for 128MB DDR2 (depending on vendor), and at $3 to $5 for the power-chip, you’ll get a minimal booting Linux box with a fully custom PCB design doing whatever you want… with a fully customized motherboard / PCB doing whatever you want.

Cool… but why would I need this?

Well, to tell you the truth… I don’t know yet. Power-constraints are the obvious benefit to running with these chips (SAM9x60 + LPDDR RAM will use 1/10th the power of a Rasp-Pi4, while still delivering a full Linux environment). But beyond that I’m still thinking in the abstract here.

I’m mostly writing this post because I’ve suddenly realized that a full custom MPU comparable to first-generation Rasp. Pi is doable by a modern hobbyist. Albeit a well studied hobbyist comfortable with trace-matched impedance controlled transmission line theory on PCBs, but I took those college-classes for a reason damn it and maybe I can actually do this.

Its a niche that 10 years ago was unthinkable for hobbyists to cheaply make their own SBCs from scratch. But today, not only is it possible, but there’s 4 or 5 different vendors (Microchip’s SAM9x60, TI’s AM355x, STM32’s STM32MP1, etc. etc.) that are catering to hobbyists with full documentation, BSPs and more. We’re no longer constrained to the designs that Rasp. Pi decides to release, we can have those 2x Ethernet ports we’ve always wanted for example (for… some reason), or build a bare-metal OS free design using only 8MB of SRAM, or use LPDDR2 low-power RAM and build a battery-operated portable device.

Full customization costs money. Whatever hobby project we do with this will cost far more than a RP4 or even RP5’s base price. But… full custom means we can build new solutions that never existed before. And the possibilities intrigue me. Full control over the full motherboard means we have absolute assurances of our power-constraints, our size, the capabilities, supporting chips and other decisions. Do you want LoRA (long-range radio?). Bam, just a module.

And you might be surprised at how much cheaper this is today than its ever been before.

Conclusion

Thanks for hearing my rant today.

This form factor is really intriguing to me and I’ll definitely be studying it moving forward as a hobby. Hopefully I’ve manage to inspire someone else out there!

I like what SiP presents for full customization of the system, but I feel this doesn’t quite fulfill the goal of the “missing middle” but rather is a half-step short of building a custom build for each project. That’s… not ideal for prototyping, if said prototype can only be met with a microprocessor.

What I’d like to see is a spectrum of embedded compute for increasing levels of complexity. So for example, the low-end of compute would be met by today’s handy and cheap microcontrollers, like the MSP430 and Atmel lineup. These would be characterized by having the “standard fare” of interfaces, like SPI and I2C, and maybe even CAN bus. But not higher order interfaces like Ethernet nor application-specific features like DSP capabilities.

The high end would be fully-customized solutions, involving board layout and EE input. This would be for late-stage development when a project is being committed for volume production, where cost and board space are at a premium. Anything and everything can be done at this end of the spectrum, and the notion of “turnkey” chips simply doesn’t exist.

Between these two extremes, I would think that the “missing middle” are a finite group of turnkey microprocessors platforms – not microcontrollers – that support the higher order interfaces, in combination with some number of unique features, like RF, DSP, real-time processing, and support for a full, virtual memory OS like Linux.

This is a broad description, because I think this middle category should be the largest. And yet, the only microprocessor platform I can think that is well-known and well-used is the RPi. Its strengths are its ubiquity and being cheap. No other Linux-capable SBC seems to hold a candle to the RPi right now.

To that end, the SAM9x60 is fantastic for widening the space for folks working in that high-end of the spectrum. But until someone or some entity produces a volume run of an SBC or drop-in module utilizing it, I can’t see why a rapid-development project inclined to use an RPi (middle end complexity) would want to incur the effort of doing their own custom design (high end complexity).

I feel like the SAM9x60D1G-I/LZB is close enough to a plug-and-play “compute module”, but you do have a point in that a compute-module isn’t quite a complete computer yet.

TI’s AM335x / Octavo OSD335x chips have a huge advantage from this particular criticism you have. These chips are behind the Beaglebone Black, meaning you have all three (Beaglebone Black / Green as a SBC for beginners, OSD335x SiP for intermediates, and finally the AM3351BZCEA60 (or other specific versions) for full customization.

At $50 for the SBC / Beaglebone Black, its a weaker buy than Rasp. Pi. But the overall environment and knowledge that Beaglebone Black represents a full ecosystem to the “expert” PCB layout (and includes an in-between SiP from Octavo systems) is surely one of the best arguments available.

Microchip obviously isn’t trying to compete against this at all, and I think that’s fine. TI’s got the full scale concept under lockdown. The SAM9x60’s chief advantage is (wtf??!?!) 4-layer prototypes for DDR2 routing. Its clearly a far simpler chip and more robust to work with. Well, that and also absurdly low power usage.