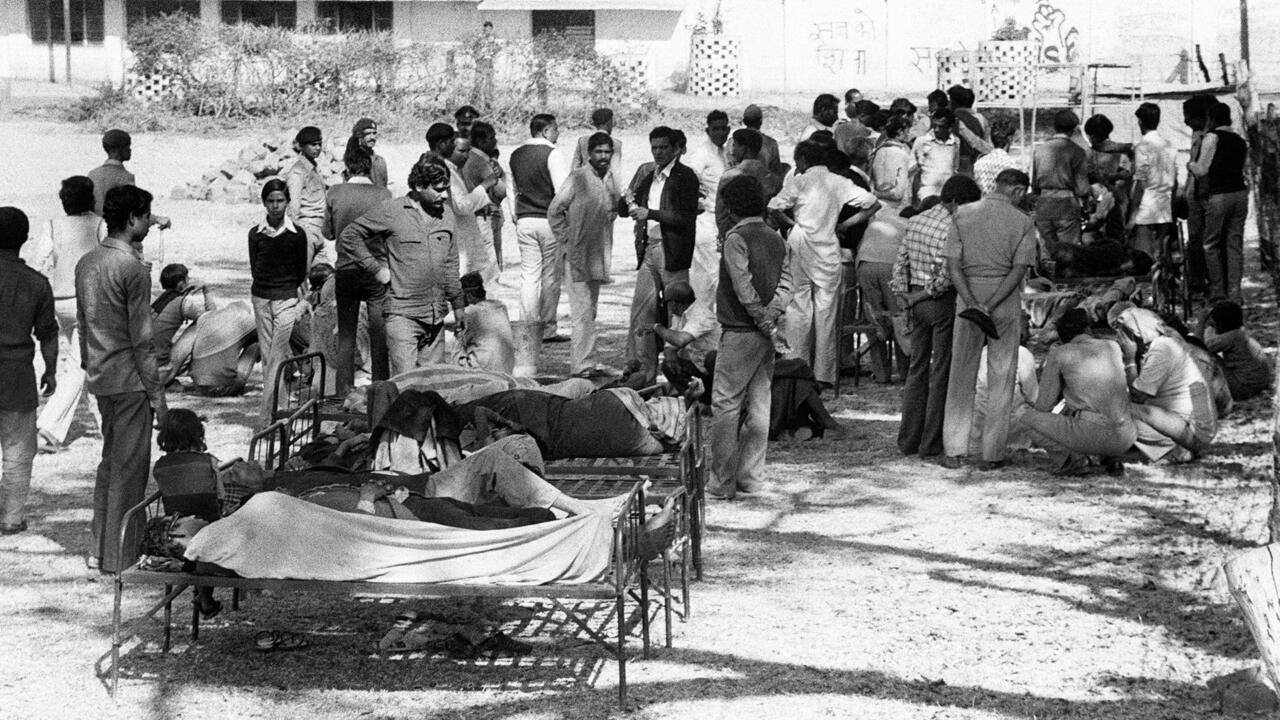

"People were frothing from their mouths, the 81-year-old recalls. “Some had defecated, some were choking in their own vomit.” His response to the deadly fumes was as brave as it was foolhardy. He tied a handkerchief over his nose and used a pushcart to ferry his neighbours to hospital.

Gas Devi was born as the poisonous plumes of smoke seeped into the city of two million souls on 2 December 1984. Four decades on, the daily wage labourer says she has constant pain in her chest, the result of a lung that has not fully developed. She complains that she keeps falling sick. […] “I believe this name is a curse. I wish I had died that night.”

Twenty-seven tonnes of methyl isocyanate (MIC), used in the production of pesticides, escaped into the cold night air after one of the tanks storing the chemical burst. As well as those who perished in the immediate aftermath, up to 25,000 people are estimated to have since died in what remains the world’s deadliest industrial disaster.

“We don’t know when the horror will end,” Rachna Dhingra, an activist who heads the Bhopal Group for Information and Action, told RFI. "Children in utero at the time of the disaster were born sick. The new generations have an alarming rate of cancer. “Bhopal didn’t happen 40 years ago. Bhopal has been going on for 40 years.”

Union Carbide’s negligence was quickly established. In 1989, in a partial out-of-court settlement with the Indian government, Union Carbide agreed to pay 450 million euros in compensation to the victims. But the victims themselves were not consulted in the negotiations, and received just 300 euros each. Dow Chemical, the current owners, have refused to pay further compensation for the catastrophe.

In 1991, Warren Anderson, Union Carbide chairman and chief executive at the time of the disaster, was charged in India with culpable homicide not amounting to murder. But he never stood trial and died aged 92 in Florida in 2014. A plea seeking compensation of 500,000 rupees (6,000 euros) from the Indian government for each victim diagnosed with cancer or kidney ailments is languishing in courts.

“Not a single individual has gone to jail – even for a day – for killing more than 25,000 people and injuring half a million people, and contaminating the soil and groundwater,” said Dhingra. “People in the city are continuing to fight because there is no legal mechanism to hold these corporations accountable worldwide.”

A report in the medical journal The Lancet published on 1 December to coincide with the 40th anniversary of the tragedy, highlighted the gruesome legacy in the capital of Madhya Pradesh state. “It is estimated that more than 150,000 people exposed to methyl isocyanate are still battling respiratory, gastrointestinal, neurological, ophthalmological or psychiatric illnesses,” the report reads.

hundreds of children seeking medical help at the Chingari Trust struggle to speak, walk or eat their meals. Rashida Bee, co-founder of the charity organisation, believes those who died were fortunate. “At least their misery ended,” she said. “The unfortunate are those who survived.”

She blames the disorders on the accident and the contamination of the groundwater. Tests of groundwater near the site has revealed cancer and birth defect-causing chemicals 50 times higher than what is accepted as safe by the Environmental Protection Agency in the United States. “This tragedy is showing no signs of relenting,” said Bee, 68, who has lost several members of her family to cancer since the accident. “The soil and water here are contaminated and that is why kids are still being born with deformities.”

Activists say that Union Carbide and Dow Chemical have been evading responsibility since December 1984. “They are using techniques known to multinationals: delaying deadlines, not going to court, refusing to recognise Indian justice as competent,” rights campaigner Satinath Sarangi told RFI.

Sarangi, 70, said the MIC fumes damaged the immune system of affected populations and caused chromosomal aberrations, something corroborated by medical research. “Children of gas-exposed parents have much higher prevalence of congenital malformations,” he said. “Bhopal has taught corporations how to get away with murder. None of those responsible have been convicted, and the US government has always opposed their extradition. This is the biggest industrial crime in history, and it goes unpunished.”

“The Bhopal disaster could have been avoided, and it could also have enabled the players involved to rectify their mistakes,” said Deb, a professor at California Polytechnic State University. “Instead, India’s state and private actors who are driven by increasing privatisation and a desire to have more foreign investment have exacerbated people’s suffering."

On Monday, campaigners organised the mass posting of thousands of victims’ letters to India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi, calling for him to take action over their claims for compensation. “The sad reality is that in India you get all the permits and escape all the controls by paying the right person,” said Sarangi.

“Today, the country is dotted with mini Bhopals, industrial zones that contaminate the local population, often from the lower castes. “But we will keep fighting because Bhopal is the biggest industrial crime in history and concerns the whole world."