- cross-posted to:

- [email protected]

- cross-posted to:

- [email protected]

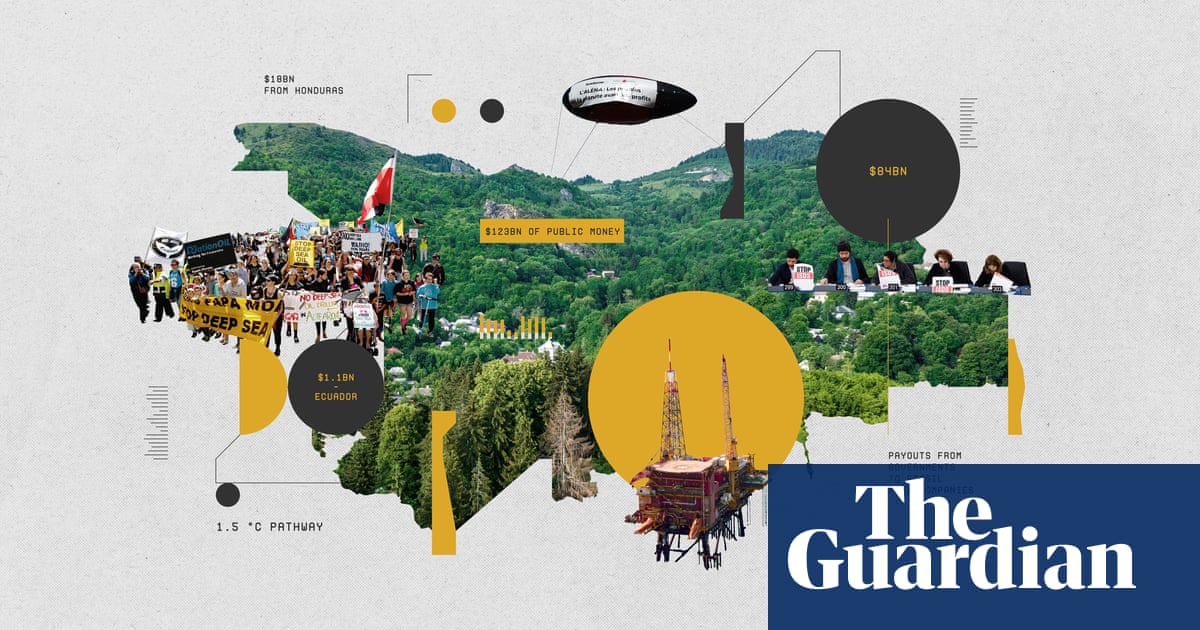

In the mountains of Transylvania, a Canadian company makes plans for a vast gold and silver mine. The proposal – which involves razing four mountain tops – sparks a national outcry, and the Romanian government pulls its support.

After protests from local communities, the Italian government bans drilling for oil within 12 miles of its shoreline. A UK fossil fuel firm has to dismantle its oilfield.

Beneath the grey whales and sea turtles of Mexico’s gulf, an underwater exploration company gets a permit to explore a huge phosphate deposit. Before it can begin, Mexico withdraws the permit, saying the ecosystem is “a natural treasure” that could be threatened by mining.

Such cases appear to be part of the bread and butter of governments – updating environmental laws or responding to voter pressure. But every time, the company involved sued the government for lost profits and often, they won (Romania prevailed in its case, Italy and Mexico were forced to pay out).

They are among more than 1,400 cases analysed by the Guardian from within the investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) system, a set of private courts in which companies can sue countries for billions. There have been long-held concerns about ISDS creating “regulatory chill” – where governments are scared off action on nature loss and the climate crisis by legal risks. Now, government ministers from a range of countries have confirmed to the Guardian that this “chilling” is already in effect – and that fear of ISDS suits is actively shaping environmental laws and regulations.

🤮