Ulaanbaatar (AFP) – As she watched her five-month-old son lying in intensive care, wires and tubes crisscrossing his tiny body, Uyanga cursed her hometown Ulaanbaatar and its chronic pollution.

The toxic smog that settles over the Mongolian capital every winter has been a suffocating problem for more than a decade that successive governments have failed to dispel.

There are wisps of hope in a resurgent grassroots movement and a promised official push to action.

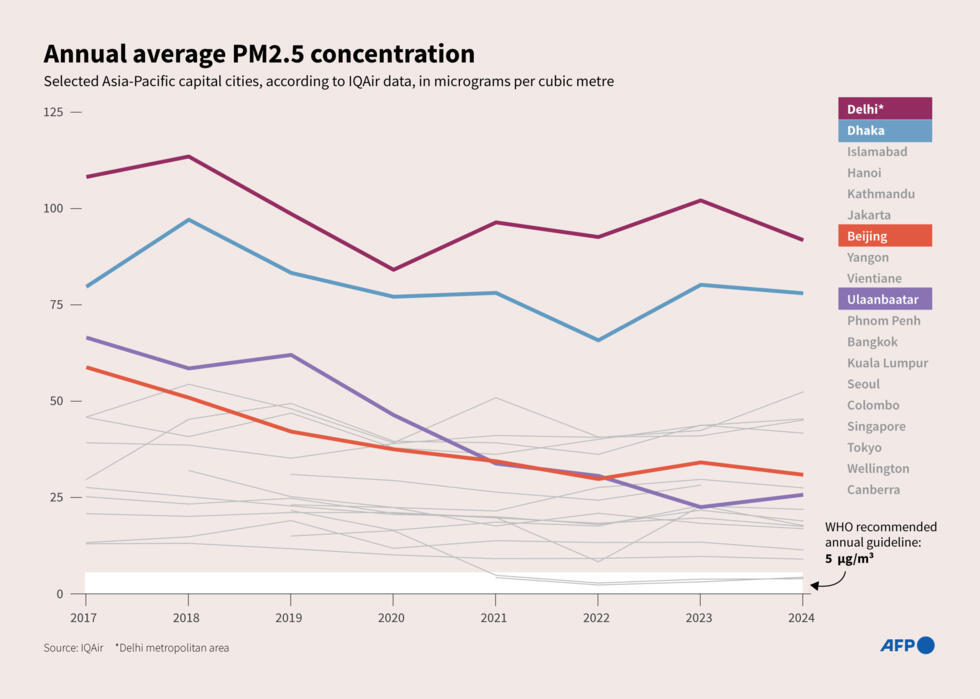

But the statistics are grim.

Respiratory illness cases have risen steadily, with pneumonia the second leading cause of death for children under five.

In the depths of winter, the city’s daily average of PM 2.5 – small particulate that can enter the lungs and bloodstream – can be 27 times higher than the level considered safe by the World Health Organization.

Young children are particularly vulnerable, breathing faster than adults and taking in more air relative to their size.

All three of Uyanga’s children were hospitalised with respiratory illnesses before they were a year old, with her youngest admitted two winters in a row.

Located in a basin surrounded by mountains, Ulaanbaatar traps smoke and fumes from both coal-guzzling power stations and homes.

A dense blanket of smog coils snugly around city-centre apartments and Mongolia’s traditional round ger tents in its outer districts most winter mornings.

Ger dwellings have sprawled as hundreds of thousands of nomads decamp to the capital in search of steadier incomes and better public services.

Most use individual coal burners to stay warm in the winter, when temperatures can plunge to minus 40 degrees Celsius (minus 40 Fahrenheit).

One freezing morning, distributors loaded up coal briquettes onto a pick-up truck whizzing around ger households.

“I don’t think there’s anyone in Mongolia who’s not concerned about air pollution,” said 67-year-old coal seller Bayarkhuu Bold.

Cashier Oyunbileg said she burns a 25-kilogramme (55-pound) bag of briquettes every two days.

Inside her ornate, cosy ger, she confessed she was “really worried” about her three children’s health, and had even set up her tent on higher ground hoping to avoid air pollution.

Her family attempted to switch to an electric heater but “just couldn’t afford the bill”.

Respiratory disease rates among children are increasing in such districts, school doctor Yanjmaa said.

“It is impossible for people who are breathing this air to have healthy lungs,” she said.

Wealthier compatriots now often choose to spend the winter outside Mongolia.

Uyanga and her husband spent their entire savings renting somewhere with better air quality for three months when their first child was born.

“It’s helpless,” she said. “No matter how hard we try to keep the indoor air quality better… our children (have to) go outside all the time.”

In 2019, the government replaced raw coal with refined coal briquettes, offering some brief air quality benefits, said state meteorologist Barkhasragchaa Baldorj.

The benefits have plateaued as coal burning increases in a country where the industry is vital to the economy.

The briquettes have also been linked to carbon monoxide poisoning and increased levels of some pollutants.

Barkhasragchaa is one of only two people assigned to Ulaanbaatar’s air quality monitoring stations.

“If you heard the actual budget allocated for maintenance, you would laugh… it’s just impossible to maintain a constant operation,” he said.

Many were sceptical about government efforts.

“Personally, I don’t see any results,” coal seller Bayarkhuu said.

The city’s deputy governor responsible for air pollution, Amartuvshin Amgalanbayar, promised change.

This year, 20,000 households will switch to gas, resulting in a 15 percent reduction in pollution, he said.

Plans to move another 20,000 households from ger districts into apartments will begin in 2025, as well as efforts to solve another of the capital’s intractable and related problems – traffic.

A long-delayed metro, that has become a symbol of official inefficacy, will be built by 2028, he said.

“The issues we were talking about trying to solve 20 years ago, when I was a student, are still here,” said the 40-year-old. “It’s been given to the next generation to solve.”

That exasperation coalesced last year when tens of thousands signed a petition demanding a public hearing on pollution policies.

…