I recently held a science slam about this topic! It’s a mix of the first computer scientists being mathematicians, who love their abbreviations, and limited screen size, memory and file size. It’s a trend in computing that has been well justified in the past, but has been making it harder for people to work together. And the need to use abbreviations has completely gone with the age of auto completion and language servers.

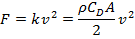

Man, I hate that so much. I swear this was half the reason I struggled with maths and physics, that these guys need to write this:

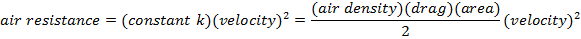

Rather than this:

At some point, they even collectively decided that not having to write a multiplication dot is more important than being able to use more than a single letter for your variables. Just what the fuck?

Thing is, you usually define all your variables. At least we do in engineering (of physical variety, rather than software).

Mostly because we can’t expect everyone reading the calculation to know, and that not everyone uses the same symbols.

Not explaining each variable is bad practice, other than for very simple things. (I do expect everyone and their dog reading a process eng calc to know PV=nRT, at a minimum).

Just like (in my opinion) not defining industry specific abbreviations is also bad practice.

I mean, it was rather physics that was worse in this regard.

Mathematicians do define their variable quite rigorously. Everything is so abstract, at some point you do just need to write down “this thing is a number”. Problem with maths folks is rather that they get more creative with their other symbols. So, “this thing is a number” is actually written as “∃x, x ∈ ℝ”.

But yeah, in the school/university physics I experienced, it was assumed that you knew that U is voltage, ρ (rho) is density, ω (omega) is angular velocity etc…

At one point, I had to memorize six pages of formulas and it felt like every letter (Latin, Greek, uppercase, lowercase, some Fraktur for good measure) was a shorthand for something.

I should specify when I say physical engineering I just mean chemical, mechanical, electrical, etc. (not software), rather than physics in theory/academia.

I guess engineers are applied physics (in a particular area each), and we need to distribute our deliverables to people who aren’t necessarily experts in every discipline.

It just also makes sense to always define variables.

It’s so funny because I’ve never seen voltage defined as U, and not V haha, proving how if you’re going to have an equation, you’d better define everything, there’s so many reused letters!

U is definitely standard for a difference in electric potential in Europe. Thought to come from “Unterschied”, difference. V refers to electric potential, which as wikipedia says so wisely, should not be confused with a difference in electric potential. Which North American notation does. At least it’s not PEMDAS…

But Nah, I think assumed knowledge of PV=nRT is fair in context, since if you don’t know what it is, you’ll only be reading the conclusion, not getting into the weeds of a calculation document.

I’m not going even going to be explaining if I have a column that’s says volumetric flow rate, with V=m/ρ. If I give mass flow rate and density (with units, of course), and use these extremely common symbols, and someone doesn’t understand, then they have no real business getting to this level of detail anyway.

I do agree that in most cases not defining your variables is bad practice, but there is some nuance, depending on the intended audience and how common a formula is, and the format of whatever it is you’re writing.

So, in the end you just do assume everyone to know the “common sense” one-letter notation for everything. Well, not everything, but the essential ten thousands of entities for sure /s

This sounds like No true Scotsman fallacy to me

I find it a bit contradicting to the very point you made about defining variables. If anything, one might be some home-grown genius that has real business getting into details but only ever used Chinese characters as variables

Understand your frustration with how I’ve communicated my position, sorry about that:

My justification for the examples I’ve given is there still needs to be other context, is based on complexity of the equation, and the intended audience of that equation.

An example of me not explaining a very simple equation would be perhaps a table of various cases:

| — | mass flow (kg/hr) | density (kg/m³) | Volumetric flow (m³/hr), V = m/ρ |

| Case 1 | blah blah | blah blah | blah |

| Etc. | … | … | … |

Realising now that markdown tables don’t seem to work 😅, hopefully this is still clear.

It may be a touch better to put variable symbols in the other columns, but:

You still have the final answer (the purpose of my report, I’m not writing a thesis here)

It should be plainly obvious by the units, and the fact those are the previous two variables, to someone who has the ability to understand (and is the intended audience of that little equation)

As a recent example for this, in a data sheet I recently prepared, I literally just put a * in the references column and said “*calculated from other data sheet values” for the volumetric flow rate, because the intended audience would know how to do that, and the purpose was for me to communicate how that value was determined.

Me putting in the V = m/ρ in the hypothetical example I gave above is a just a little mind jog for the reader.

Where more complicated equations are used, of course these are properly referenced, usually even with the standard or book it’s come from.

I’ll redefine my position to:

Clearly define all variables, unless it’s abundantly obvious to your intended audience from context.

My intended audience of the conclusions or final values are the layman. My intended audience of everything else is someone with a very basic chemical engineering understanding.

Your last point is a strawman:

I find it a bit contradicting to the very point you made about defining variables. If anything, one might be some home-grown genius that has real business getting into details but only ever used Chinese characters as variables

Because I’m writing in English, for an English speaking audience, and there is no such thing as a home-grown genius getting into my area because it’s a legal requirement that they have an honours degree. Even still, the two assumed knowledge equations I mentioned, which I would only not reference with sufficient context, would STILL be recognisable with totally random symbols.

| mass flow (kg/hr) | density (kg/m³) | Volumetric flow (m³/hr), 容 = 质/密 |

Yup, a bit odd in an English context, but with the units information (always mandatory, of course) completely understandable.

First of all, thank you for a thoughtful response, I was too snarky, sorry about that.

TL;DR: guess I’m just upset that there is no objective way of measuring how much knowledge is required, and trying to read everything from sources list would take forever.

Yeah, the last point is sort of a strawman, although I meant it not to highlight that explanations should be given in terms that the reader is used to, but rather that the reader may have quite arbitrary amount of prior knowledge.

I agree that there probably should be some shared context, what bugs me is that people tend to vary a lot in what amount of context is considered to be required. And more than once have I met papers that require deciphering even if you have some context and kind of come from the field they are written for. I used to think that this is our of malice to make reproducing their work harder for others, but maybe it was just an assumption of much larger shared context.

Tables markdown work in some clients, afaik, but I don’t remember which, and even if I saw it or imagined it

In another thread I admit I didn’t explain my position here well enough. I would only not explain this equation given sufficient context (e.g. I’ve shown all those variables in a table, and my intended audience is people familiar with basic chemistry, which I’d expect would be everyone reading the report for this particular example, since this is high school chemistry, and the topic of all reports I work on is chemical engineering.)

People can read the conclusions if they’re not familiar with chemistry, and for the detail, they’re not my intended audience anyway.

Generally I still hold the position that you should define variables as much as possible, unless it’s overly cumbersome, given your intended audience would clearly understand anyway.

In context this simple equation is obvious even if you change the symbols, as long as there is sufficient context to draw from.

Using full names like that might be fine for explaining a physical rule, or stating the final result of some calculation - but it certainly would be cumbersome and difficult for actually carrying out the calculations. In many cases we already fill pages with algebra showing how things can be related and rearranged to arrive at new results. That kind of work would be intractable with full word names for the variables, partially because you’d be constantly spilling off the end of the page trying to write the steps; but also because having all that stuff would actually obfuscate what you are trying to do - which is algebra. And during that process, the meanings and values of the pronumerals is not as important has how they interact with each other. So the names are just a distraction.

For setting up an equation, and for stating the final result, the meanings of the variables are very important; but during the process of manipulating the equations to get the result you want the meanings of the letters are often ignored. You only need to know that it is something that can be multiplied, or inverted, or subtracted, or whatever. Eg. suppose I want to rearrange to get the velocity. I don’t care that I’m dividing both sides by the air density times the drag coefficient and the area… I’m just dividing ρCA, which is an algebraic blob whose interpretation can be saved for some other time.

This is absolutely true, but it still seems to me that we’re throwing the baby out with the bath water when we just stick to extremely terse symbols for everything regardless of context.

Reading articles would be so much easier if they used even slightly longer names – thankfully more and more computer science articles do tend to use more human readable naming nowadays, at least.

Sure, longer names make manipulation harder a bit more annoying if you’re doing it by hand, but if you do need to manipulate something you can then abbreviate the terms (and I’m 60% sure I’ve seen some papers that had both a longer form and a shorter form for terms, so one for explaining shit and one for the fiddly formal stuff)

Of course using terse terms is totally fine when it’s clear from the context what eg. ∆x means.

Yep, that’s what it usually boils down to. However, I think a slight approach shift for basic materials could be useful, where introductory books / papers / … write out formulas. That makes it easier to understand the basic concepts before moving onto the more complex stuff. It should be easy to create such works, as they are usually created digitally, and autocomplete is available. Students can and will abbreviate those written outs words by themselves (after all, writing is annoying), but IMO reading comprehension is the key part that can be improved.

Also, when doing long formulas that you want to eliminate members of, writing stuff out can be a nightmare.

Bruh how large should our notebook pages be? Also how should we speak about the equation?

What if the terms should be represented in a matrix? What if mathematical functions e^x, sin, ln etc. are present? Would you write sine of e^(velocity of the particle B) ? Notations are necessary for readability

I don’t know what to tell you. They obliterate readability for me.

I also genuinely believe these shorthands hinder access to research for the 99.9% of humanity who are not experts in the given field. Obviously, you do need to understand the context to use a formula correctly, but that also becomes harder when everything is written with hieroglyphs.

In university, I had to assess this paper. It took me 3 weeks to decipher that alien language, and it doesn’t even say anything particularly riveting.

To address your points:

I’m hoping that at least published math can be typed out with full names.

I’m not opposed to local aliases. E.g. if the point is that some values in the matrix are negative and others not, then absolutely write “with air_resistance as ‘a’, the catapultation matrix is { a, -a, -a, … }”.

I don’t actually want to introduce spaces into variable names, that’s just an example I randomly found online. I was rather thinking e.g. sine(euler^velocity_b).

Bonus point: You can reasonably type it on a computer, because you don’t need Greek letters and subscripts anymore.

Btw i am all for local aliases. I see them most of the times.

i.e, [equation], where a = area of the surface,

v= velocity,…

But without short codes it would be a pain to write and remember. Some of the shortening like del operator really reallh simplifies the original expression with better showcase of physical meaning, but looks alien to people who don’t know. But we can’t stop using it since it makes everything else difficult for people in that area

You only have to define it once in a document, book, whatever. Also, it’s not like you’d ever need to do this for handwritten notes, only for a wider audience, or if you intend for something to be read by not just you.

No one is suggesting you don’t use symbols, just that you define them, and not assume the reader uses the same symbols as you. Which, so often, they don’t. (How many different ones have you come across just in highschool and uni. I came across multiple)

I’m no physicist, but surely there is a huge range of symbols for the same thing, especially the more niche you get.

I’m not a mathematician, but I agree with you because this is precisely how one would abbreviate repeating terms in a paper (e.g. The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and the Metropolitan Museum of Art (The Met) are both located in New York, New York (colloquially, New York City, or NYC). While MoMA has an art collection of about 200,000 pieces, The Met houses 1.5 million works of art.)

Welcome to Greece!

No, not our modern Greece, the old timey write philosophical questions into the dirt with sticks and argue with your best homies about it kind of Greece!

Want to compute something? Hope you got all your steps in linear order so you don’t have to remember too much in between other steps!

/s (but not really so I totally am on your side, original formulations of math problems are a pain…)

It’s been really holding me back in learning coding. I felt pretty comfortable at first learning javascript, but as I got further the code was increasingly hard to look back to and understand, to the point I had to spend a lot of time understanding my own code.

Does it truely matter after the code has been compiled if it has more full words or not?

It matters as soon as a requirement change comes in and you have to change something. Writing a dirty ass incomprehensible, but working piece of code is ok, as long as no one touches it again.

But as soon as code has to be reworked, worked on together by multiple people, or you just want to understand what you did 2 weeks earlier, code readability becomes important.

I like Uncle Bobs Clean Code (with a grain of salt) for a general idea of what such an approach to make code readable could look like. However, it is controversial and if overdone, can achieve the opposite. I like it as a starting point though.

Did you know that in the first version of php, each function name would be hashed to lookup the code to run it? And the hashing algorithm was: the first letter. So all the functions started with a different letter.

It’s not. PHP used to use the function length as hash buckets, so by having evenly distributed lengths the execution time was faster. No idea where GP came up with that.

GP specifically talked about the first version of PHP, sounds like it was just a dummy implementation as they were working on PHP, that then later got replaced with a proper implementation :)

And with a bit of namespacing and/or object orientation and usage of dots, it becomes perfectly readable.

There are also camel case and underscores in other languages…

BTW: How on earth should a newcomer know that the letter “n” in that word stands for number without having to google it? The newcomer could even assume that it’s a letter of the word string… And even, if you know that it stands for number, it’s still hard for me to understand what it means in this context… I actually had to google it… But that’s probably some C++ convention I don’t know about, because I don’t program in C++…

How on earth should a newcomer know that the letter “n” in that word stands for number without having to google it?

By looking at the difference between strcpy and strncpy. Preferably, though, you should simply learn C before writing C.

The gist of is is that strcpy takes a null-terminated string and copies it somewhere, while strncpy takes a zero-terminated string and copies it somewhere but will not write more than n bytes. strncpy literally has exactly one more parameter than strcpy, that being n, hence the name. If n is smaller than the string length (as in: distance to first null byte) then you’re bound to have garbage in your destination, and to check for that you have to dereference the pointer strncpy returns and check if it’s actually null. Yay C error handling.

In retrospect null-terminated strings were a mistake, but so were many other things, at some point you just have to accept that there’s hysterical raisins everywhere.

If n is smaller than the string length (as in: distance to first null byte) then you’re bound to have garbage in your return destination

Wha? N is just maximum length of string to copy. Data after dst+n is unchanged.

In retrospect null-terminated strings were a mistake, but so were many other things, at some point you just have to accept that there’s hysterical raisins everywhere.

Sure but that means the part before that is garbage because you have a null terminated string without terminator.

Or at least that’s how I see it. If your intention isn’t to start and end with a null-terminated string you should be using memcpy. Let us not talk about situations where CHAR_BIT!=8 that’s not POSIX anyway.

Even better, just avoid doing string manipulation in C.

Why are they even named like this?

When I read code, I want to be able to read it…

Is this from a time when space was expensive and you wanted to reduce the space of the source files on the devs PC???

For me (with a native language != english), this made it a lot harder to get into programming in the first place.

I recently held a science slam about this topic! It’s a mix of the first computer scientists being mathematicians, who love their abbreviations, and limited screen size, memory and file size. It’s a trend in computing that has been well justified in the past, but has been making it harder for people to work together. And the need to use abbreviations has completely gone with the age of auto completion and language servers.

Man, I hate that so much. I swear this was half the reason I struggled with maths and physics, that these guys need to write this:

Rather than this:

At some point, they even collectively decided that not having to write a multiplication dot is more important than being able to use more than a single letter for your variables. Just what the fuck?

Thing is, you usually define all your variables. At least we do in engineering (of physical variety, rather than software).

Mostly because we can’t expect everyone reading the calculation to know, and that not everyone uses the same symbols.

Not explaining each variable is bad practice, other than for very simple things. (I do expect everyone and their dog reading a process eng calc to know PV=nRT, at a minimum).

Just like (in my opinion) not defining industry specific abbreviations is also bad practice.

Mathematicians don’t do this? Shame on them.

I mean, it was rather physics that was worse in this regard.

Mathematicians do define their variable quite rigorously. Everything is so abstract, at some point you do just need to write down “this thing is a number”. Problem with maths folks is rather that they get more creative with their other symbols. So, “this thing is a number” is actually written as “∃x, x ∈ ℝ”.

But yeah, in the school/university physics I experienced, it was assumed that you knew that U is voltage, ρ (rho) is density, ω (omega) is angular velocity etc…

At one point, I had to memorize six pages of formulas and it felt like every letter (Latin, Greek, uppercase, lowercase, some Fraktur for good measure) was a shorthand for something.

I should specify when I say physical engineering I just mean chemical, mechanical, electrical, etc. (not software), rather than physics in theory/academia.

I guess engineers are applied physics (in a particular area each), and we need to distribute our deliverables to people who aren’t necessarily experts in every discipline.

It just also makes sense to always define variables.

It’s so funny because I’ve never seen voltage defined as U, and not V haha, proving how if you’re going to have an equation, you’d better define everything, there’s so many reused letters!

Thanks for sharing

U is definitely standard for a difference in electric potential in Europe. Thought to come from “Unterschied”, difference. V refers to electric potential, which as wikipedia says so wisely, should not be confused with a difference in electric potential. Which North American notation does. At least it’s not PEMDAS…

There ya go (only used it up until highschool physics, in Australia, iirc), I definitely have no business reading anything regarding voltage then 😅

Thanks for sharing

Still bad, i’m not a computer with a lookup table in memory.

What is “eng”?

Lol fair point regarding Eng: “Engineering”.

But Nah, I think assumed knowledge of PV=nRT is fair in context, since if you don’t know what it is, you’ll only be reading the conclusion, not getting into the weeds of a calculation document.

I’m not going even going to be explaining if I have a column that’s says volumetric flow rate, with V=m/ρ. If I give mass flow rate and density (with units, of course), and use these extremely common symbols, and someone doesn’t understand, then they have no real business getting to this level of detail anyway.

I do agree that in most cases not defining your variables is bad practice, but there is some nuance, depending on the intended audience and how common a formula is, and the format of whatever it is you’re writing.

So, in the end you just do assume everyone to know the “common sense” one-letter notation for everything. Well, not everything, but the essential ten thousands of entities for sure /s

This sounds like No true Scotsman fallacy to me

I find it a bit contradicting to the very point you made about defining variables. If anything, one might be some home-grown genius that has real business getting into details but only ever used Chinese characters as variables

Edit: forgot to set language

Understand your frustration with how I’ve communicated my position, sorry about that:

My justification for the examples I’ve given is there still needs to be other context, is based on complexity of the equation, and the intended audience of that equation.

An example of me not explaining a very simple equation would be perhaps a table of various cases:

| — | mass flow (kg/hr) | density (kg/m³) | Volumetric flow (m³/hr), V = m/ρ | | Case 1 | blah blah | blah blah | blah | | Etc. | … | … | … |

Realising now that markdown tables don’t seem to work 😅, hopefully this is still clear.

It may be a touch better to put variable symbols in the other columns, but:

As a recent example for this, in a data sheet I recently prepared, I literally just put a * in the references column and said “*calculated from other data sheet values” for the volumetric flow rate, because the intended audience would know how to do that, and the purpose was for me to communicate how that value was determined.

Me putting in the V = m/ρ in the hypothetical example I gave above is a just a little mind jog for the reader.

Where more complicated equations are used, of course these are properly referenced, usually even with the standard or book it’s come from.

I’ll redefine my position to: Clearly define all variables, unless it’s abundantly obvious to your intended audience from context.

My intended audience of the conclusions or final values are the layman. My intended audience of everything else is someone with a very basic chemical engineering understanding.

Your last point is a strawman:

Because I’m writing in English, for an English speaking audience, and there is no such thing as a home-grown genius getting into my area because it’s a legal requirement that they have an honours degree. Even still, the two assumed knowledge equations I mentioned, which I would only not reference with sufficient context, would STILL be recognisable with totally random symbols.

| mass flow (kg/hr) | density (kg/m³) | Volumetric flow (m³/hr), 容 = 质/密 | Yup, a bit odd in an English context, but with the units information (always mandatory, of course) completely understandable.

First of all, thank you for a thoughtful response, I was too snarky, sorry about that.

TL;DR: guess I’m just upset that there is no objective way of measuring how much knowledge is required, and trying to read everything from sources list would take forever.

Yeah, the last point is sort of a strawman, although I meant it not to highlight that explanations should be given in terms that the reader is used to, but rather that the reader may have quite arbitrary amount of prior knowledge.

I agree that there probably should be some shared context, what bugs me is that people tend to vary a lot in what amount of context is considered to be required. And more than once have I met papers that require deciphering even if you have some context and kind of come from the field they are written for. I used to think that this is our of malice to make reproducing their work harder for others, but maybe it was just an assumption of much larger shared context.

Tables markdown work in some clients, afaik, but I don’t remember which, and even if I saw it or imagined it

What’s PV? Asking for my friend’s dog.

(Pressure) * (volume) = (# moles) * (gas constant) * (temperature)

The ideal gas law.

In another thread I admit I didn’t explain my position here well enough. I would only not explain this equation given sufficient context (e.g. I’ve shown all those variables in a table, and my intended audience is people familiar with basic chemistry, which I’d expect would be everyone reading the report for this particular example, since this is high school chemistry, and the topic of all reports I work on is chemical engineering.)

People can read the conclusions if they’re not familiar with chemistry, and for the detail, they’re not my intended audience anyway.

Generally I still hold the position that you should define variables as much as possible, unless it’s overly cumbersome, given your intended audience would clearly understand anyway.

In context this simple equation is obvious even if you change the symbols, as long as there is sufficient context to draw from.

Using full names like that might be fine for explaining a physical rule, or stating the final result of some calculation - but it certainly would be cumbersome and difficult for actually carrying out the calculations. In many cases we already fill pages with algebra showing how things can be related and rearranged to arrive at new results. That kind of work would be intractable with full word names for the variables, partially because you’d be constantly spilling off the end of the page trying to write the steps; but also because having all that stuff would actually obfuscate what you are trying to do - which is algebra. And during that process, the meanings and values of the pronumerals is not as important has how they interact with each other. So the names are just a distraction.

For setting up an equation, and for stating the final result, the meanings of the variables are very important; but during the process of manipulating the equations to get the result you want the meanings of the letters are often ignored. You only need to know that it is something that can be multiplied, or inverted, or subtracted, or whatever. Eg. suppose I want to rearrange to get the velocity. I don’t care that I’m dividing both sides by the air density times the drag coefficient and the area… I’m just dividing ρCA, which is an algebraic blob whose interpretation can be saved for some other time.

This is absolutely true, but it still seems to me that we’re throwing the baby out with the bath water when we just stick to extremely terse symbols for everything regardless of context.

Reading articles would be so much easier if they used even slightly longer names – thankfully more and more computer science articles do tend to use more human readable naming nowadays, at least.

Sure, longer names make manipulation harder a bit more annoying if you’re doing it by hand, but if you do need to manipulate something you can then abbreviate the terms (and I’m 60% sure I’ve seen some papers that had both a longer form and a shorter form for terms, so one for explaining shit and one for the fiddly formal stuff)

Of course using terse terms is totally fine when it’s clear from the context what eg. ∆x means.

Try to write the above with pen and ink and then tell me if you can read it back yourself.

Single letters is not a good system but it was the less bad one.

Yep, that’s what it usually boils down to. However, I think a slight approach shift for basic materials could be useful, where introductory books / papers / … write out formulas. That makes it easier to understand the basic concepts before moving onto the more complex stuff. It should be easy to create such works, as they are usually created digitally, and autocomplete is available. Students can and will abbreviate those written outs words by themselves (after all, writing is annoying), but IMO reading comprehension is the key part that can be improved.

Also, when doing long formulas that you want to eliminate members of, writing stuff out can be a nightmare.

I don’t have to write with pen and paper anymore though

/s?

Nope.

Bruh how large should our notebook pages be? Also how should we speak about the equation? What if the terms should be represented in a matrix? What if mathematical functions e^x, sin, ln etc. are present? Would you write sine of e^(velocity of the particle B) ? Notations are necessary for readability

I don’t know what to tell you. They obliterate readability for me.

I also genuinely believe these shorthands hinder access to research for the 99.9% of humanity who are not experts in the given field. Obviously, you do need to understand the context to use a formula correctly, but that also becomes harder when everything is written with hieroglyphs.

In university, I had to assess this paper. It took me 3 weeks to decipher that alien language, and it doesn’t even say anything particularly riveting.

To address your points:

Bonus point: You can reasonably type it on a computer, because you don’t need Greek letters and subscripts anymore.

Btw i am all for local aliases. I see them most of the times.

i.e, [equation], where a = area of the surface, v= velocity,…

But without short codes it would be a pain to write and remember. Some of the shortening like del operator really reallh simplifies the original expression with better showcase of physical meaning, but looks alien to people who don’t know. But we can’t stop using it since it makes everything else difficult for people in that area

You only have to define it once in a document, book, whatever. Also, it’s not like you’d ever need to do this for handwritten notes, only for a wider audience, or if you intend for something to be read by not just you.

No one is suggesting you don’t use symbols, just that you define them, and not assume the reader uses the same symbols as you. Which, so often, they don’t. (How many different ones have you come across just in highschool and uni. I came across multiple)

I’m no physicist, but surely there is a huge range of symbols for the same thing, especially the more niche you get.

I’m not a mathematician, but I agree with you because this is precisely how one would abbreviate repeating terms in a paper (e.g. The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and the Metropolitan Museum of Art (The Met) are both located in New York, New York (colloquially, New York City, or NYC). While MoMA has an art collection of about 200,000 pieces, The Met houses 1.5 million works of art.)

Welcome to Greece! No, not our modern Greece, the old timey write philosophical questions into the dirt with sticks and argue with your best homies about it kind of Greece!

Want to compute something? Hope you got all your steps in linear order so you don’t have to remember too much in between other steps!

/s (but not really so I totally am on your side, original formulations of math problems are a pain…)

Try writing 20 algebraic manipulations of the equation on paper and you’ll quickly understand why it’s written that way.

The bottom is absolutely not more readable, and it’s much more difficult to work with.

It’s been really holding me back in learning coding. I felt pretty comfortable at first learning javascript, but as I got further the code was increasingly hard to look back to and understand, to the point I had to spend a lot of time understanding my own code.

Does it truely matter after the code has been compiled if it has more full words or not?

It matters as soon as a requirement change comes in and you have to change something. Writing a dirty ass incomprehensible, but working piece of code is ok, as long as no one touches it again.

But as soon as code has to be reworked, worked on together by multiple people, or you just want to understand what you did 2 weeks earlier, code readability becomes important.

I like Uncle Bobs Clean Code (with a grain of salt) for a general idea of what such an approach to make code readable could look like. However, it is controversial and if overdone, can achieve the opposite. I like it as a starting point though.

It’s from a time keyboards were so hard that you needed to do push ups on your finger tips if you wanted to endure a 9 to 5 programming job.

The reason people love IBM Model Ms nowadays is because the springs have been worn in now and can easily be pressed without additional training.

Kids these days have it so easy, pshh

I recall reading somewhere the earlier compilers had a hard limit on the length of function names, due to memory constraints.

I’ve heard it’s because old screens were like 60 character wide

Also punched cards had around 80 columns, which put a hard limit on the number of characters per line.

Did you know that in the first version of php, each function name would be hashed to lookup the code to run it? And the hashing algorithm was: the first letter. So all the functions started with a different letter.

I hope this is not true

It’s not. PHP used to use the function length as hash buckets, so by having evenly distributed lengths the execution time was faster. No idea where GP came up with that.

GP specifically talked about the first version of PHP, sounds like it was just a dummy implementation as they were working on PHP, that then later got replaced with a proper implementation :)

No it is, only 26 functions in total.

The Chinese had it way easier.

strncpy becomes stringnumbercopy. You can see why short version is used.

And with a bit of namespacing and/or object orientation and usage of dots, it becomes perfectly readable.

There are also camel case and underscores in other languages…

BTW: How on earth should a newcomer know that the letter “n” in that word stands for number without having to google it? The newcomer could even assume that it’s a letter of the word string… And even, if you know that it stands for number, it’s still hard for me to understand what it means in this context… I actually had to google it… But that’s probably some C++ convention I don’t know about, because I don’t program in C++…

By looking at the difference between

strcpyandstrncpy. Preferably, though, you should simply learn C before writing C.The gist of is is that

strcpytakes a null-terminated string and copies it somewhere, whilestrncpytakes a zero-terminated string and copies it somewhere but will not write more thannbytes.strncpyliterally has exactly one more parameter thanstrcpy, that beingn, hence the name. Ifnis smaller than the string length (as in: distance to first null byte) then you’re bound to have garbage in your destination, and to check for that you have to dereference the pointerstrncpyreturns and check if it’s actually null. Yay C error handling.In retrospect null-terminated strings were a mistake, but so were many other things, at some point you just have to accept that there’s hysterical raisins everywhere.

Wha? N is just maximum length of string to copy. Data after dst+n is unchanged.

All hail length-prefixed strings!

Sure but that means the part before that is garbage because you have a null terminated string without terminator.

Or at least that’s how I see it. If your intention isn’t to start and end with a null-terminated string you should be using memcpy. Let us not talk about situations where

CHAR_BIT != 8that’s not POSIX anyway.Even better, just avoid doing string manipulation in C.

Yeah, let’s not talk about 20-bit one’s complement ints.

man strncpyRemoved by mod

Why not just add function overloading to the language and have a function named

copythat takes a string and an optional character count?