- cross-posted to:

- politicsunfiltered

- cross-posted to:

- politicsunfiltered

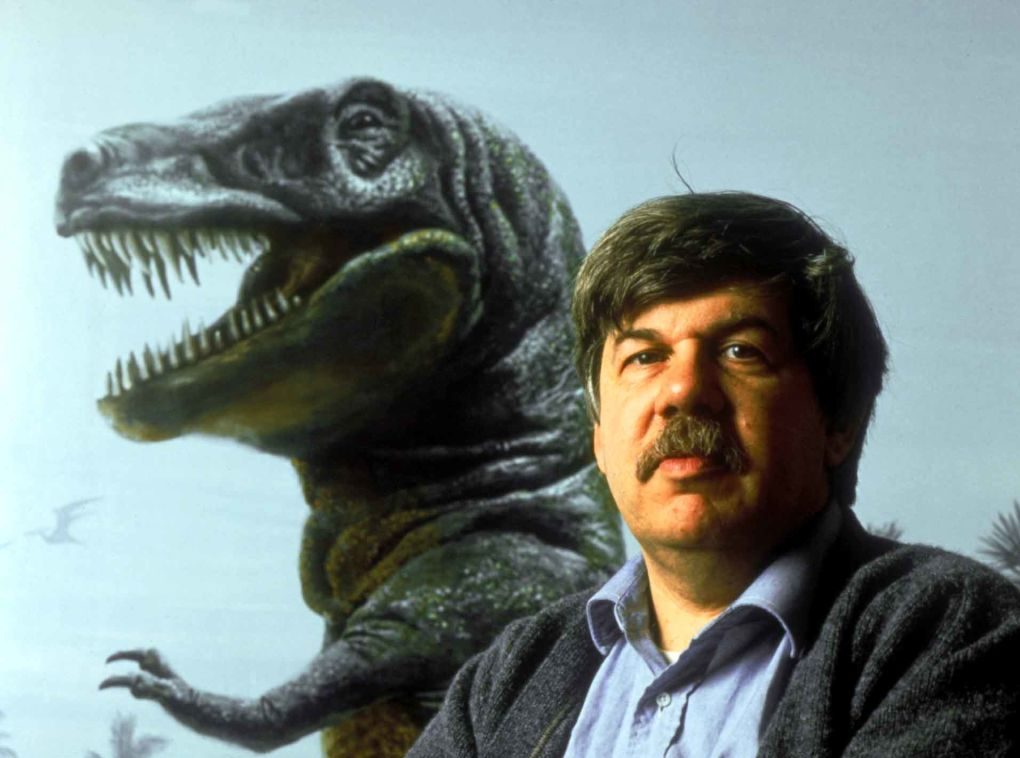

The American evolutionary biologist and historian of science Stephen Jay Gould’s column for Natural History magazine began as a way to balance the political convictions of his civil rights experiences with his desire to revolutionize evolutionary theory. As his career soared to new heights in later decades, his professional ambitions eventually eclipsed his leftist politics. But in the late 1970s, he was still using the column to address contemporary debates over science and politics. In the spring of 1976, he decided to weigh in on a controversy close to home with a column titled “Biological Potential vs. Biological Determinism,” which joined in the leftist criticism of the biologist Edward O. Wilson’s 1975 book Sociobiology: The New Synthesis.

By then, he and Wilson had been colleagues in Harvard’s biology department for several years. At first glance, Wilson’s book might not have appeared to be the most likely candidate to spark leftist outrage. It was a long academic volume that synthesized empirical work on a host of animal taxa with the aim of clarifying a new program for the evolutionary study of social behavior. Wilson was convinced that the qualities of social life — e.g., aggression, cooperation, and hierarchies — were as much a product of natural selection as were physical traits. And in what would become an infamous last chapter, he extended this argument to the study of human societies. The book was far more empirically grounded in its treatment of human evolution than the popular works of Robert Ardrey, Konrad Lorenz, and Desmond Morris, which had fed into narratives of inevitable race war at the height of civil rights activism. Nevertheless, Sociobiology was at the heart of the most consequential debate between the leftist and liberal perspectives on science and American democracy of the era.

Wilson’s writings became a flash point as a new set of evolutionary models of sex difference clashed with the political demands of an intense phase of the American women’s movement. New legal triumphs that guaranteed the right to contraception for married couples, the right to abortion, and protections against sex-based discrimination were counterbalanced by a ferociously energetic conservative Christian movement that fought against the Equal Rights Amendment and any possibility of changing women’s place in American society. Even as women across the country reimagined their roles at home, at work, and at church — and pushed for the legal protections to do so — reactionary politics continually insisted on limiting what women could do and be.

It was in the midst of this political tumult that Wilson’s book (alongside other texts on the evolution of social behavior, including Richard Dawkins’s 1976 The Selfish Gene) promoted a new evolutionary narrative that claimed that contemporary American gender roles were the products of prehistoric adaptations encoded in humanity’s genes. Sociobiologists like Wilson and Dawkins envisioned a prehistoric past in which women gathered food and lived in family camps, while men went out to hunt and seek new sexual partners. In subsequent decades, scientists and nonscientists alike would deploy this narrative in both scientific and popular settings to rationalize gender disparities in STEM fields and the workplace and to naturalize rape. Gould’s criticism of Wilson was joined by critiques developed by other leftists from the sciences and the humanities, who viewed sociobiology as reactionary politics rather than sound science. And the sustained protest against the sexism of sociobiology over the next two decades would be led by the leaders of feminist science collectives, including Ruth Hubbard, a biologist at Harvard, and Ethel Tobach, a psychologist at the American Museum of Natural History.

Before sending his column on sociobiology to Natural History for publication, Gould sent a draft of it to Wilson. Wilson’s outraged reply and the subsequent exchange between the two men reveals far more than just the contours of their personal animosity. As expressed in his letters to Gould and in later publications, Wilson had a more classically liberal view of science’s proper role in American democracy. Liberals view science as truthful knowledge that serves as a foundation for an enlightened society to guarantee equality and enact rational governance. Thus, they consider science essential for democracy, but they do not prioritize a democratic approach to the actual practice of science. As liberals see it, even when science is only done and understood by a few elite white men, the reliability of its knowledge of the natural world enables it to be the foundation of an equitable society.

This understanding of science and democracy was unacceptable to Gould, as well as to other leftists in the radical and feminist science circles that protested Wilson’s book. Although their understanding of science for the people was by no means consistent, members of these movements shared a conviction that the elitism of science impeded its capacity to support democracy. For leftists, the inclusion of women and minoritized racial groups in the professional practice of science was essential if science was to contribute to a progressive society. Wilson, for his part, characterized the attacks by Gould and others in what became known as the Sociobiology Study Group (SSG) as an attempt to restrict the freedom of scientific research and a worrisome sign of intellectual censorship.

By the end of the century, many public scientific liberals would castigate both Gould’s historical accounts of scientific racism and the feminist accounts of gender bias in science as “anti-scientific.” But the history of this late 1970s moment reveals that neither Gould nor feminist scientists saw their criticisms of sociobiology as anti-science. In fact, they understood the debate to be a conversation within the scientific community about the evidence for a new model within evolutionary science.

They believed that a better science, one that acknowledged the pitfalls of gender and racial bias, could be achieved through collective self-reflection on the motivations and practices of scientific work. And this better science could, in turn, be used to combat what these leftist academics feared were reactive and oppressive political actions. Their willingness to address the role of social influence in science and to publicly criticize current scientific research, however, set the stage for a new cultural divide. By the end of the century, sociobiology had claimed the mantle of scientific authority on human sexuality. And feminist and other leftist academics struggled to stave off accusations that their approach to scientific knowledge was itself anti-scientific.

La usona evolua biologo kaj historiisto de scienco Stephen Jay Gould komencis sian kolonon por la magazino Natural History kiel maniero ekvilibrigi la politikajn konvinkojn formitajn de liaj civitanrajtoj-spertoj kun lia deziro revoluciigi la evoluoteorion. Dum lia kariero atingis novajn altecojn en postaj jardekoj, liaj profesiaj ambicioj fine superis liajn maldekstrajn politikojn. Tamen, en la malfruaj 1970-aj jaroj, li ankoraŭ uzis sian kolonon por trakti aktualajn debatojn pri scienco kaj politiko. Printempe de 1976, li decidis kontribui al diskuto proksima al lia medio per kolono titolita “Biologia Potencialo kontraŭ Biologia Determinismo,” kiu aliĝis al la maldekstra kritiko de la biologo Edward O. Wilson kaj lia libro Sociobiology: The New Synthesis (1975).

Tiutempe, Gould kaj Wilson estis kolegoj en la biologia fakultato de Harvard dum pluraj jaroj. Je unua rigardo, la libro de Wilson eble ne ŝajnis la plej verŝajna kandidato por ekigi maldekstran koleron. Ĝi estis longa akademia verko, kiu sintetizis empiriajn esplorojn pri vasta gamo da animalaj taksonoj kun la celo klarigi novan programon por la evolua studo de socia konduto. Wilson kredis, ke la ecoj de socia vivo — ekzemple agreso, kunlaboro, kaj hierarkioj — estas same produktoj de natura selektado kiel fizikaj trajtoj. En sia jam fama lasta ĉapitro, li aplikis ĉi tiun argumenton al la studo de homaj socioj. La libro estis multe pli empiria en sia traktado de homa evoluo ol la popularaj verkoj de Robert Ardrey, Konrad Lorenz, kaj Desmond Morris, kiuj subtenis rakontojn pri neevitebla rasa milito dum la pinto de civitanrajtoj-aktivismo. Tamen, Sociobiology staris ĉe la centro de la plej grava debato inter la maldekstraj kaj liberalaj perspektivoj pri scienco kaj usona demokratio de tiu epoko.

La verkoj de Wilson fariĝis konfliktofonto, ĉar nova aro de evoluaj modeloj pri seksa diferenco koliziis kun la politikaj postuloj de intensa fazo de la usona virinmovado. Novaj juraj venkoj, kiuj garantiis la rajton al kontraŭkoncipiloj por geedzaj paroj, la rajton al aborto, kaj protektojn kontraŭ seksbazita diskriminacio, estis kontraŭpezitaj de furioza konservativa kristana movado, kiu batalis kontraŭ la Amendo pri Egalaj Rajtoj kaj ajna ŝanco ŝanĝi la lokon de virinoj en usona socio. Eĉ dum virinoj tra la lando reimagis siajn rolojn hejme, en la laborejo, kaj en la preĝejo — kaj puŝis por la juraj protektoj por fari tion — reago-politikoj konstante insistis pri limigo de tio, kion virinoj povis fari kaj esti.

Meze de ĉi tiu politika tumulto, la libro de Wilson (kune kun aliaj tekstoj pri la evoluo de socia konduto, inkluzive de The Selfish Gene de Richard Dawkins el 1976) antaŭenigis novan evoluan rakonton, kiu asertis, ke la nunaj usonaj genraj roloj estis produktoj de prahistoriaj adaptiĝoj enradikiĝintaj en la genoj de la homaro. Sociobiologoj kiel Wilson kaj Dawkins imagis prahistorian pasintecon, en kiu virinoj kolektis manĝaĵon kaj vivis en familiaj kampadejoj, dum viroj iris ĉasi kaj serĉi novajn seksajn partnerojn. En postaj jardekoj, sciencistoj kaj nesciencistoj same uzis ĉi tiun rakonton en kaj sciencaj kaj popularaj kuntekstoj por raciigi genrajn malegalecojn en STEM-kampoj kaj la laborejo kaj por naturaligi seksperforton. La kritiko de Gould pri Wilson aliĝis al la kritikoj de aliaj maldekstruloj el la sciencoj kaj homsciencoj, kiuj vidis sociobiologion kiel reagema politiko anstataŭ valida scienco. Kaj la daŭraj protestoj kontraŭ la seksismo de sociobiologio en la sekvaj du jardekoj estis gvidataj de la gvidantoj de feministaj scienckolektivoj, inkluzive de Ruth Hubbard, biologo ĉe Harvard, kaj Ethel Tobach, psikologo ĉe la Amerika Muzeo de Natura Historio.

Antaŭ ol sendi sian kolonon pri sociobiologio al Natural History por publikigo, Gould sendis skizon al Wilson. La kolera respondo de Wilson kaj la posta interŝanĝo inter la du viroj rivelas multe pli ol nur la konturojn de ilia persona malamikeco. Kiel esprimite en siaj leteroj al Gould kaj en postaj publikaĵoj, Wilson havis pli klasike liberalan vidon pri la rolo de scienco en usona demokratio. Liberaluloj vidas sciencon kiel veran scion, kiu servas kiel fundamento por klerigita socio por garantii egalecon kaj efektivigi racian regadon. Tiel, ili konsideras sciencon esenca por demokratio, sed ili ne prioritatas demokratan aliron al la efektiva praktiko de scienco. Por liberaluloj, eĉ kiam scienco estas nur praktikata kaj komprenata de kelkaj elitoj, ĝia fidindeco pri la natura mondo permesas ĝin esti la fundamento de justeca socio.

Tiu kompreno pri scienco kaj demokratio estis neakceptebla por Gould, same kiel por aliaj maldekstruloj en la radikalaj kaj feministaj sciencocirkloj, kiuj protestis kontraŭ la libro de Wilson. Kvankam ilia kompreno pri “scienco por la popolo” ne estis konsekvenca, membroj de ĉi tiuj movadoj kundividis la konvinkon, ke la elitisma naturo de scienco malhelpis ĝian kapablon subteni demokration. Por maldekstruloj, la inkludo de virinoj kaj minoritataj rasaj grupoj en la profesia praktiko de scienco estis esenca por ke scienco kontribuu al progresema socio. Wilson, siavice, karakterizis la atakojn de Gould kaj aliaj el la Sociobiologia Studgrupo (SSG) kiel provo limigi la liberecon de scienca esplorado kaj kiel zorgiga signo de intelekta cenzuro.

Ĉe la fino de la jarcento, multaj publikaj sciencaj liberaluloj kondamnis kaj la historiajn rakontojn de Gould pri scienca rasismo kaj la feministajn rakontojn pri genra biaso en scienco kiel “kontraŭsciencajn.” Sed la historio de ĉi tiu momento en la malfruaj 1970-aj jaroj montras, ke nek Gould nek feministaj sciencistoj vidis siajn kritikojn pri sociobiologio kiel kontraŭsciencajn. Fakte, ili komprenis la debaton kiel konversacion ene de la scienca komunumo pri la evidenteco por nova modelo en evolua scienco.

Ili kredis, ke pli bona scienco, kiu agnoskas la malavantaĝojn de genra kaj rasa biaso, povus esti atingita per kolektiva memreflektado pri la motivoj kaj praktikoj de scienca laboro. Kaj ĉi tiu pli bona scienco povus, siavice, esti uzata por batali kontraŭ tio, kion ĉi tiuj maldekstraj akademiuloj timis esti reagema kaj subprema politika ago. Ilia preteco trakti la rolon de socia influo en scienco kaj publike kritiki nunajn sciencajn esplorojn tamen starigis la scenejon por nova kultura disiĝo. Ĉe la fino de la jarcento, sociobiologio akiris la mantelon de scienca aŭtoritato pri homa sekseco. Kaj feministaj kaj aliaj maldekstraj akademiuloj luktis por eviti akuzojn, ke ilia aliro al scienca scio mem estis kontraŭscienca.